Bhajan Hunjan (b. 1956) was the 2020 Artist in Residence at Projecto Maria Lucia Cattani, Brazil. https://marialuciacattani.wordpress.com/

Link to exhibition catalogue here: https://www.marialuciacattani.com/publications-publicacoes.html

This initiative celebrates the life and work of the highly respected Brazilian artist, Maria Lucia Cattani, (1958-2015). Artist Nick Rands has invited a succession of artists and curators to respond to his late wife’s work, to use her Porto Alegre studio and to mount joint exhibitions of their own work and hers, selected from the archive of her work.

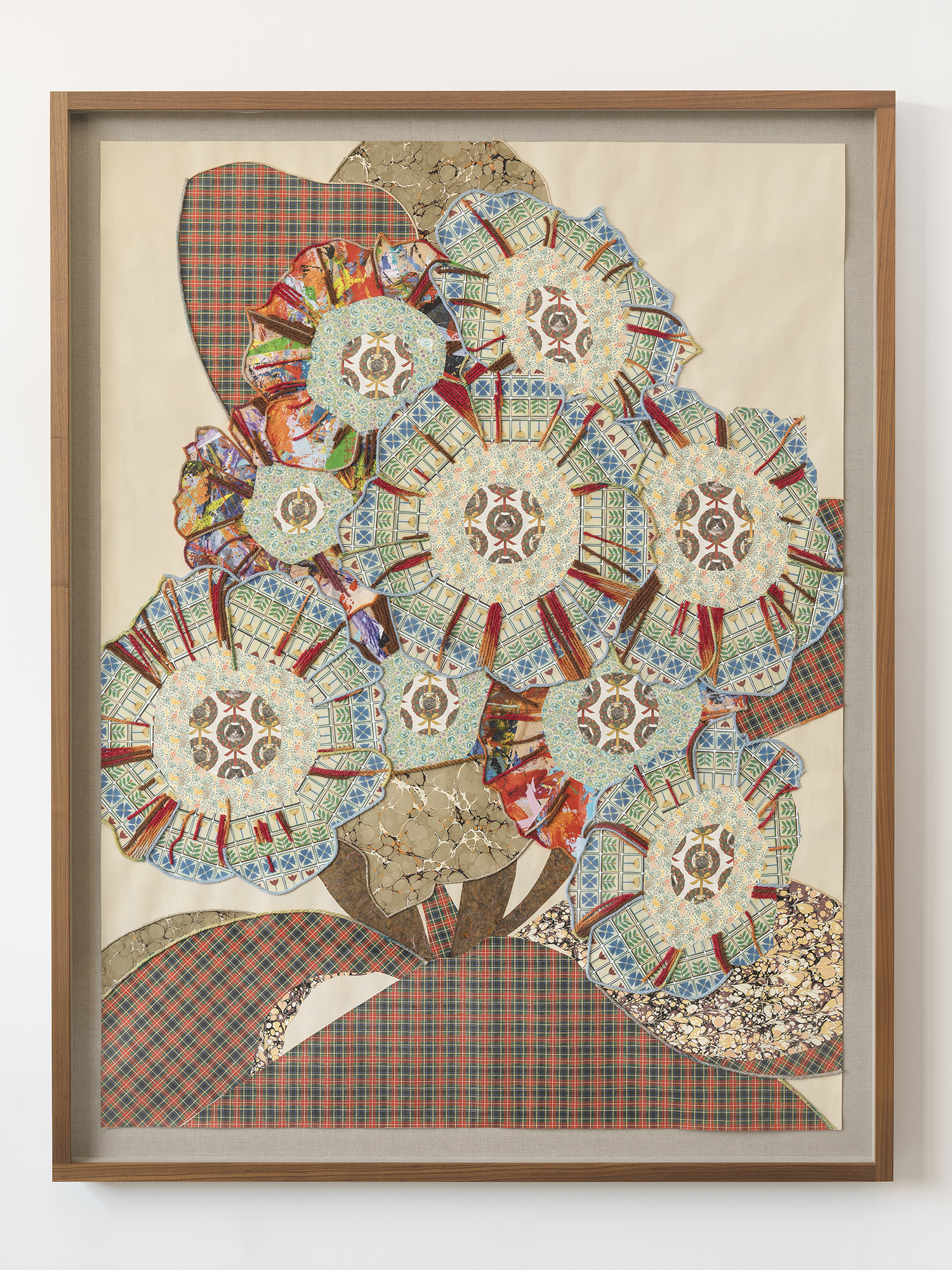

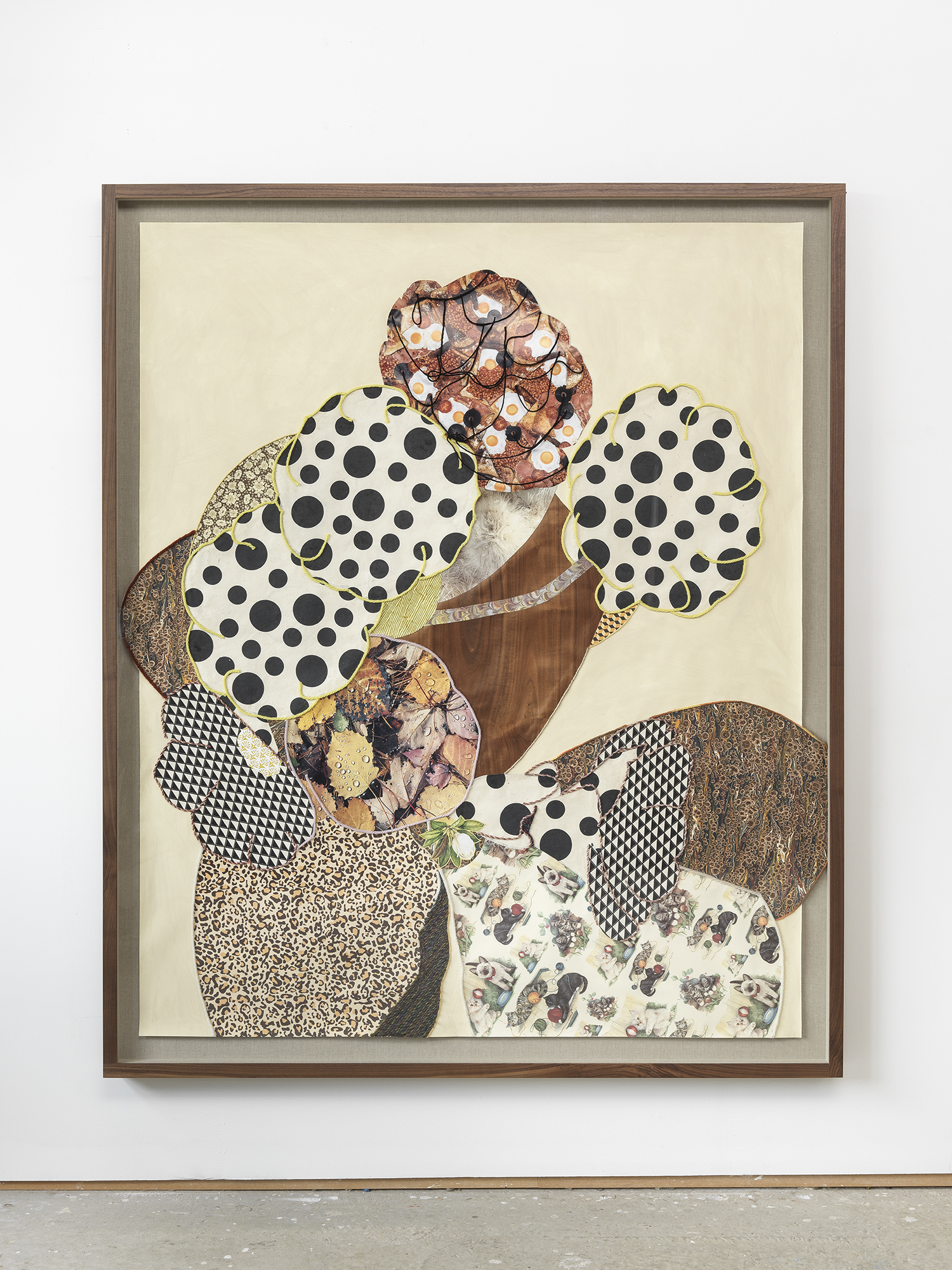

Bhajan was invited in part because she knew Maria Lucia as a friend and fellow artist when they were both based in Reading in the 1990s, while Maria Lucia was researching her PhD at University of Reading. There were parallels in their practice – both produced works on paper using a variety of print techniques. Both were dedicated teachers – Maria Lucia as Head of Printmaking at University of Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre, Brazil, Bhajan as an artist educator with young people of all ages creating temporary and permanent installations in schools and community environments[1]. Both had an enduring interest in architecture: Maria Lucia frequently used the wall as matrix and support alike, printing upon and carving into its surface, producing an immersive, sensory wraparound; Bhajan has made site-specific permanent features for external and internal spaces, frequently informed by the location and the local community. Each artist derived inspiration from their immigrant cultural backgrounds: Maria Lucia’s family migrated from Italy to Brazil in the 19th Century; Bhajan’s to England in the 1960s via Kenya from Punjab (now divided between India and Pakistan). They each acknowledge the influence of textile works and ‘repetitive and patient’ tasks undertaken by their women ancestors.[2]

For the residency, due to Covid restrictions on travel, Bhajan was obliged to familiarise herself with Maria Lucia’s work only through catalogue and web images. What is it like to investigate another’s practice so closely, to examine their motivations and their influences, and yet have to do so at great distance and through the filter of reproduction? Bhajan studied reproductions closely and allowed their principles to inform a new area of practice. She found a language of soft mark-making which was derived from a spiritual connection with the work and from memories of the artist herself: a person of remarkable energy, warmth and generosity.

Bhajan focussed on the ‘script works’ produced by Maria Lucia from the early 2000s, in prints, in laser-cut artworks, in books, and much later applied directly in ink upon the wall. Maria Lucia’s script is highly distinctive, confident and delivered without hesitation, but intentionally illegible. Influenced by an early study of Sumerian cuneiform and entranced by the notion of a block as the bearer of a cursive form, she printed and overprinted in massed multiples, using colour and rotation in strict and not-so-strict ‘systems’. These could cover an entire wall or be presented in small, folded book-forms or print on paper. She had been impressed by the beauty and ‘neutral visual appeal’ of Japanese script on her 2001 trip to Awaji, Japan, and in practices akin to the ‘allusive field of writing’ of Cy Twombly, the ‘Patterned Utterance’ of Susan Hillier[3], began to extend her mark-making into more script-like forms, presenting in horizontal lines, experimenting with marks made with both her right and left hand.

Connecting Script, 2021

Bhajan chose to interact with this area of Maria Lucia’s work, whilst making it very much her own. Deriving inspiration from Sikh Gurbani scriptures from the Punjab, and while listening to the sacred music often sung to specific ragas. Bhajan used a Gurmukhi script[4] in a repetitious, meditative way, enjoying free, cursive mark-making. She says, “As I was writing them, I was trying to put across the essence of the sound (because for me they have a sound and meaning) and the inspiration and elation I feel when I listen to that sound.” Initially this was on a square support which was cut into smaller units. Before being used for relief printing (3 x 3 Linocuts, 2021), this surface was disrupted and abstracted, through an intuitive but rationalised and numbered rearrangement inspired by Maria Lucia’s systematic approach. What seems like simple repetition is disrupted by changes in colour and print pressure, systems of rotation, reduction printing and new pairings of cursive forms. Bhajan embraces accident as well as the structured approach of Maria Lucia: “You can be playful,” she says, “but at the same time there is strict process to it and that creates a different piece of work at the end of the day… I guess that’s the way our lives work – we think we have a plan, and we work through that plan in a very rational way, but where we end up is quite a surprise.” [5]

In a less systematic and rotational way Bhajan printed longer and more fluid blocks of script, which in turn were repeated across multiple sheets of fine paper, and sometimes bound into book form. These are repeated prints and presented as multiples, but they are not editioned; each one has a unique combination of density of inking; of harmonious and complementary pigment, in rich blues, reds and gold, in monoprinted ground colour and figured overprinting. Conjoined, they provide a rhythmic undulation, a punctuated repetition, where comparison is invited and sustained viewing is rewarded with a sensuous satisfaction. (Connecting Script, linocut on monoprint on paper, and Continuous Script, linocut on Nepalese paper, both 2021).

3 x 3 Lino on Archival Paper

Bhajan has said that her intensive study of Maria Lucia’s work led her not only to further investigation into repetition and the creative use of script, but also to a revived interest in colour. As a result, the works from this residency resonate with rich pigment, deployed in complementary transparency and opacity, each applied layer of printing activating its neighbours and its bedfellows.

This correspondence, both material and intellectual, over time and over continents, is apt and richly satisfying. It is enacted between two women artists with a shared interest in print and paper, in repetition, in the power of script, whether legible or not, as a carrier of deeper and spiritual meaning. Bhajan Hunjan has risen to the challenge of a creative response with an intimacy of interpretation, and yet without imitation. She has devised a unique and meaningful visual language which remains creatively and culturally distinct whilst acknowledging and celebrating the work of another.

Sara Roberts

2019 Curator in Residence, Projeto Maria Lucia Cattani, Brazil

[1] https://bhajanhunjan.com/about/ (accessed 2 December 2022)

[2] Film 2, https://marialuciacattani.wordpress.com/artist-diary-bhajan-hunjan/ (accessed 2 December 2022)

[3] See Roberts, S., Regras e Suas Exeções/Rules and their Exceptions, Maria Lucia Cattani, in the monograph Maria Lucia Cattani, UFRGS, Departamento de Difusão Cultural, 2019.

[4] The phonetic writing of Punjabi Sikhs derived from Guru Anghad in the early 16th C, written from left to right and phonetically; as opposed to Shahmukhi, a Perso-Arabic script first used by the Muslim Sufi Poets from the 12th C, written from right to left, currently used by Punjabi Muslims.

[5] Film 8, https://marialuciacattani.wordpress.com/artist-diary-bhajan-hunjan/ (accessed 2 December 2022)